Rational trigonometry

Rational trigonometry is a recently introduced approach to trigonometry that eschews all transcendental functions (such as sine and cosine) and all proportional measurements of angles. In place of angles, it characterizes the separation between lines by a quantity called the "spread", which is a rational function of their slopes. In place of the classical transcendental functions, it introduces a number of "laws" between the lengths and spreads of lines bound by various geometric configurations, notably triangles.

Rational trigonometry was introduced by Prof. Norman J. Wildberger in his 2005 book Divine Proportions: Rational Trigonometry to Universal Geometry. The book is purposefully critical of traditional mathematics. One of the main claims the author makes is that the field of trigonometry is being taught and applied using choices in measurements and relations (such as angles and transcendental functions) that are arbitrarily complicated, are not necessary in order to reason about most concepts of the field, nor are they needed for most practical applications.

The author proposes new basic measurements on which to base the field itself and related applications (namely, the square of distance instead of the plain distance between two points, and the spread instead of the angle between two lines) and goes on to prove an array of theorems and laws to work with these measurements.

From there, the author rebuilds a great part of Euclidean geometry on top of his new proposed measurements, using only rational equivalences, which allow him to avoid any assumptions about the underlying scalar field. This is the Universal Geometry part of the book, where most classical findings of geometry are shown to be applicable to any field, including the field of rational numbers or finite fields.

Wildberger holds a Ph.D. in mathematics from Yale University, and taught at Stanford University from 1984 to 1986 and at the University of Toronto from 1986 to 1989; he is currently an associate professor of mathematics at the University of New South Wales, Australia.

Contents |

Quadrance and spread

Instead of distance and angle, rational trigonometry uses as its fundamental units quadrance (square of distance) and spread (square of sine of angle).[1] This choice of variables enables calculations to produce output results whose complexity matches that of the input data. For instance, in a typical trigonometry problem if rational numbers are assigned to all quadrances and spreads, then the calculated results will be rational numbers (or roots of rational numbers).

This rationality is obtained at the expense of linearity. Unlike the traditional distance and angle units, doubling or halving a quadrance or spread does not double or halve a length or a rotation. Similarly, the sum of two lengths or rotations is not the sum of their individual quadrances or spreads.

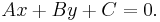

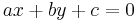

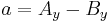

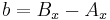

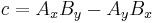

For distinction, Wildberger refers to the traditional trigonometry as classical trigonometry. It is otherwise broadly based on Cartesian analytic geometry, with a point defined as an ordered pair (x, y) and a line as a general linear equation

The mathematics of rational trigonometry is, applications aside, a special instance of the description of geometry in terms of linear algebra (using rational methods such as dot products and quadratic forms), but students who are first learning trigonometry are often not taught about the use of linear algebra in geometry. Changing this state of affairs is a stated aim of Wildberger's book (to paraphrase his comments).

Trigonometry over arbitrary fields

Rational trigonometry makes it possible to do trigonometry over any field, not just the field of real numbers.[2]

Quadrance

The quadrance is the square of the distance.[1]

Quadrance and distance are concerned with the separation of points. Quadrance differs from standard distance in that it squares the distance. Most immediately, this means that calculating the distance (or, more accurately, quadrance) between two points in 2-dimensional space is easier, as there is no need to find the square root of the sum of the squares of the differences in the x and y coordinates.

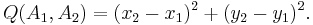

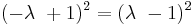

In the (x, y)-plane, the quadrance Q(A1, A2) for the points A1 and A2 is defined as

Spread

Spread, a measure of the separation of lines, is a dimensionless number in the range [0, 1]. The value of the spread is the square of the sine of the angle.[1]

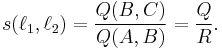

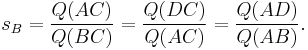

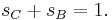

Suppose two lines, ℓ 1 and ℓ 2, intersect at the point A as shown at right. Choose a point B ≠ A on ℓ 1 and let C be the foot of the perpendicular from B to ℓ 2. Then the spread s is

Spread compared to angle

In rational trigonometry, spread is a fundamental concept, somewhat but not precisely corresponding to the concept in traditional geometry of angle. Spread describes a relationship between two lines, whereas angle describes a relationship between two rays emanating from a common point.[1]

The spread is the square of the sine of the angle.

| Degree | Radian | Spread |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | (1/6)π | 1/4 |

| 45 | (1/4)π | 1/2 |

| 60 | (1/3)π | 3/4 |

| 90 | (1/2)π | 1 |

| 120 | (2/3)π | 3/4 |

| 135 | (3/4)π | 1/2 |

| 150 | (5/6)π | 1/4 |

| 180 | π | 0 |

Spread is not proportional to degrees or radians, and has a period of 180 degrees (π radians).

Laws of rational trigonometry

Wildberger states that there are five basic laws in rational trigonometry. He also states, correctly, that these laws can be verified using high-school level mathematics. Some are equivalent to standard trigonometrical formulae with the variables expressed as quadrance and spread.[1]

In the following five formulas, we have a triangle made of three points A1, A2, A3, . The spreads of the angles at those points are s1, s2, s3, , and Q1, Q2, Q3, are the quadrances of the triangle sides opposite A1, A2, and A3, respectively. As in classical trigonometry, if we know three of the six elements s1, s2, s3, , Q1, Q2, Q3, and these three are not the three s', then we can compute the other three.

Triple quad formula

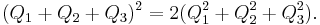

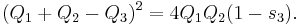

The three points A1, A2, A3, are collinear if an only if:

This formula comes from applying is equivalent to using Heron's formula, the condition for collinearity being that the triangle formed by the three points has zero area.

It can either be proved by analytic geometry (the preferred means within rational trigonometry) or derived from Heron's formula, using the condition for collinearity that the triangle formed by the three points has zero area.

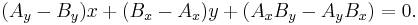

The line  has the general form:

has the general form:

where the (non-unique) parameters a, b and c, can be expressed in terms of the coordinates of points A and B as:

so that, everywhere on the line:

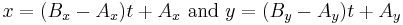

But the line can also be specified by two simultaneous equations in a parameter t, where t = 0 at point A and t = 1 at point B:

or, in terms of the original parameters:

and

and

If the point C is collinear with points A and B, there exists some value of t (for distinct points, not equal to 0 or 1), call it λ, for which these two equations are simultaneously satisfied at the coordinates of the point C, such that:

and

and

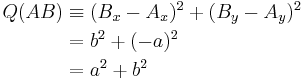

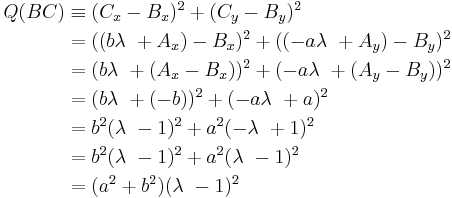

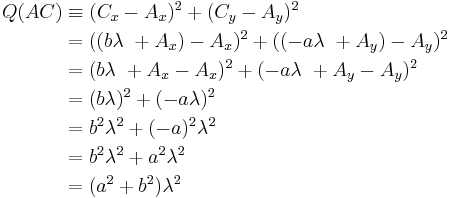

Now, the quadrances of the three line segments are given by the squared differences of their coordinates, which can be expressed in terms of λ:

where use was made of the fact that  .

.

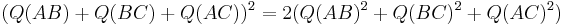

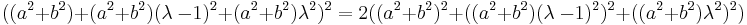

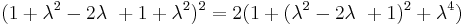

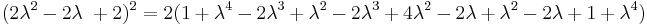

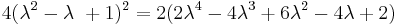

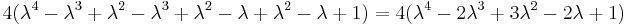

Substituting these quadrances into the equation to be proved:

Now, if  and

and  represent distinct points, such that

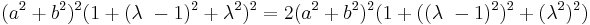

represent distinct points, such that  is not zero, we may divide both sides by

is not zero, we may divide both sides by  :

:

Pythagoras' theorem

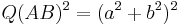

The lines A1A3 (of quadrance Q1) and A2A3 ((of quadrance Q2)) are perpendicular (their spread is 1) if and only if:

where Q3 is the quadrance between A1 and A2.

This is equivalent to the Pythagorean theorem plus the inverse of the Pythagorean theorem.

There are many classical proofs of Pythagoras' theorem; this one is framed in the terms of rational trigonometry.

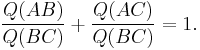

The spread of an angle is the square of its sine. Given the triangle ABC with a spread of 1 between sides AB and AC,

where Q is the "quadrance", i.e. the square of the distance.

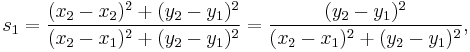

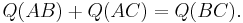

Construct a line AD dividing the spread of 1, with the point D on line BC, and making a spread of 1 with DB and DC. The triangles ABC, DBA and DAC are similar (have the same spreads but not the same quadrances).

This leads to two equations in ratios, based on the spreads of the sides of the triangle:

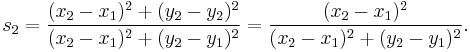

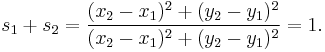

Now in general, the two spreads resulting from dividing a spread into two parts, as line AD does for spread CAB, do not add up to the original spread since spread is a non-linear function. So we first prove that dividing a spread of 1, results in two spreads that do add up to the original spread of 1.

For convenience, but with no loss of generality, we orient the lines intersecting with a spread of 1 to the coordinate axes, and label the dividing line with coordinates  and

and  . Then the two spreads are given by:

. Then the two spreads are given by:

Hence:

So that:

Using the first two ratios from the first set of equations, this can be rewritten:

Multiplying both sides by  :

:

Spread law

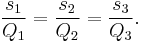

For any triangle  with non zero quadrances:

with non zero quadrances:

This is the law of sines, just squared.

Cross law

For any triangle  ,

,

This is analogous to the law of cosines. It is called 'cross law' because  , the square of the cosine of the angle, is called the 'cross'.

, the square of the cosine of the angle, is called the 'cross'.

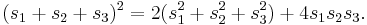

Triple spread formula

For any triangle

This corresponds (roughly) to the angle sum formulae for sine and cosine. If we know two of the spreads, this allows us to compute the third one. To do this we need to solve a second-degree equation, so it is more inconvenient than the analogue in classical trigonometry.

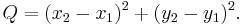

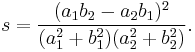

Calculating quadrance and spread

Given the coordinates of two points (x1, y1) and (x2, y2), the quadrance between them is

Given two lines whose equations are a1x + b1y = constant and a2x + b2y = constant, the spread between them is

Ease of calculation

Rational trigonometry makes some problems solvable with only addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, with fewer uses of other functions such as square roots, sine, and cosine (compared with classical trigonometry). Such algorithms execute more efficiently on most computers, for problems such as solving triangles. Other computations, (such as computing the quadrance of a line segment given the quadrance of two collinear line segments which compose it, or such as computing the spread of the sum of two angles with known spreads) do involve more computations than their classical analogues.[3]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Wildberger, Norman J. (2007). "A Rational Approach to Trigonometry". Math Horizons (Washington, DC: Mathematical Association of America) November 2007: 16–20. ISSN 1072-4117

- ^ Le Anh Vinh, Dang Phuong Dung (July 17, 2008). Explicit tough Ramsey graphs. arXiv:arXiv:0807.2692, page 1. Another version of this article is at Le Anh Vinh, Dang Phuong Dung (2008), "Explicit tough Ramsey Graphs", Proceedings of International Conference on Relations, Orders and Graphs: Interaction with Computer Science 2008, Nouha Edtions, 139–146. }}

- ^ Olga Kosheleva (2008), "Rational trigonometry: computational viewpoint", Geombinatorics, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 18–25.

- Wildberger's rational trigonometry site, including downloadable papers and sections of his book

- A comparison of classical and rational trigonometry

- Alexander Bogomolny (2007). "A brief introduction to Rational Trigonometry". Cut-the-knot. http://www.cut-the-knot.org/pythagoras/RationalTrig/CutTheKnot.shtml.